AT 42-05 | 26 November 2018

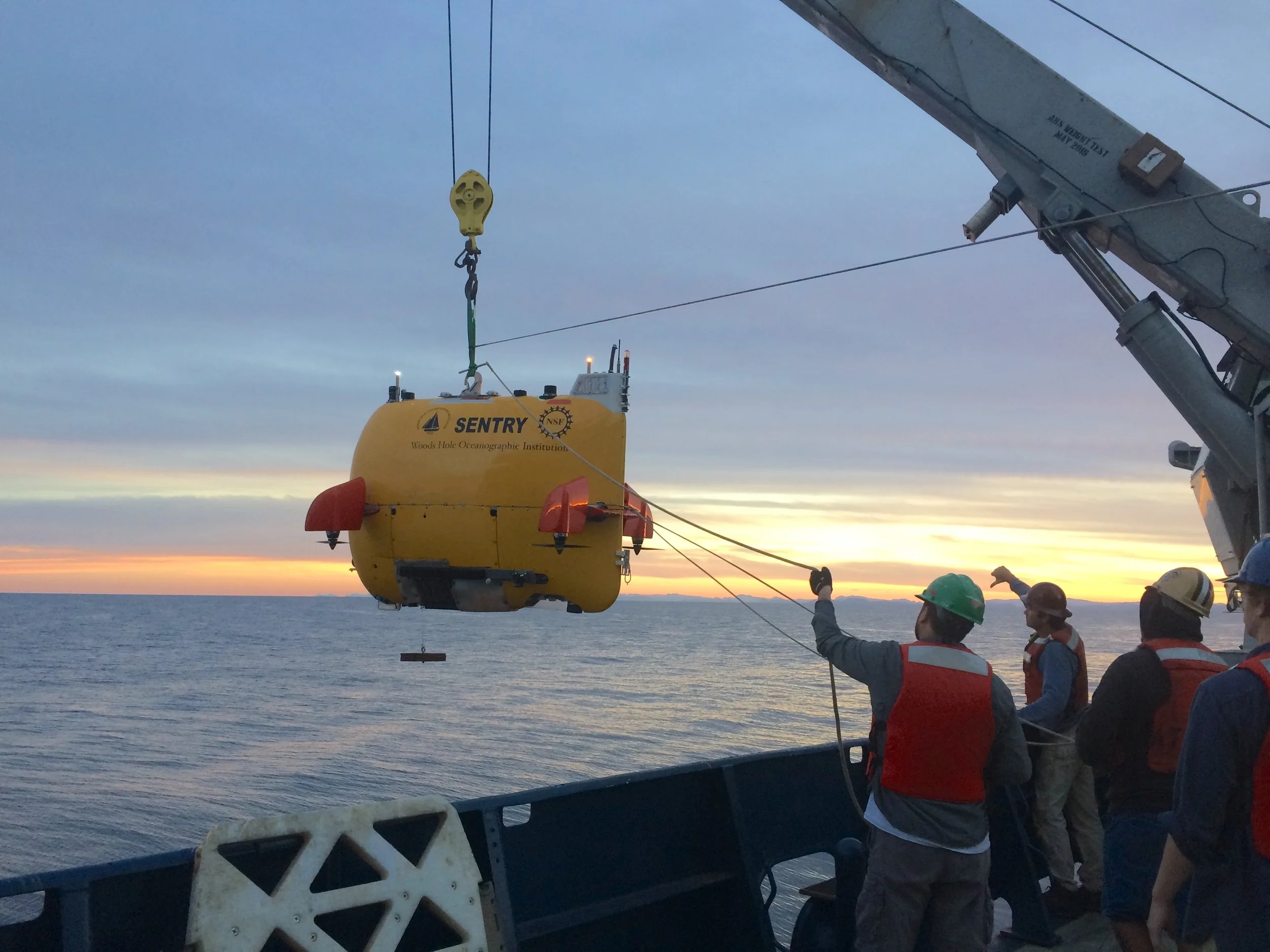

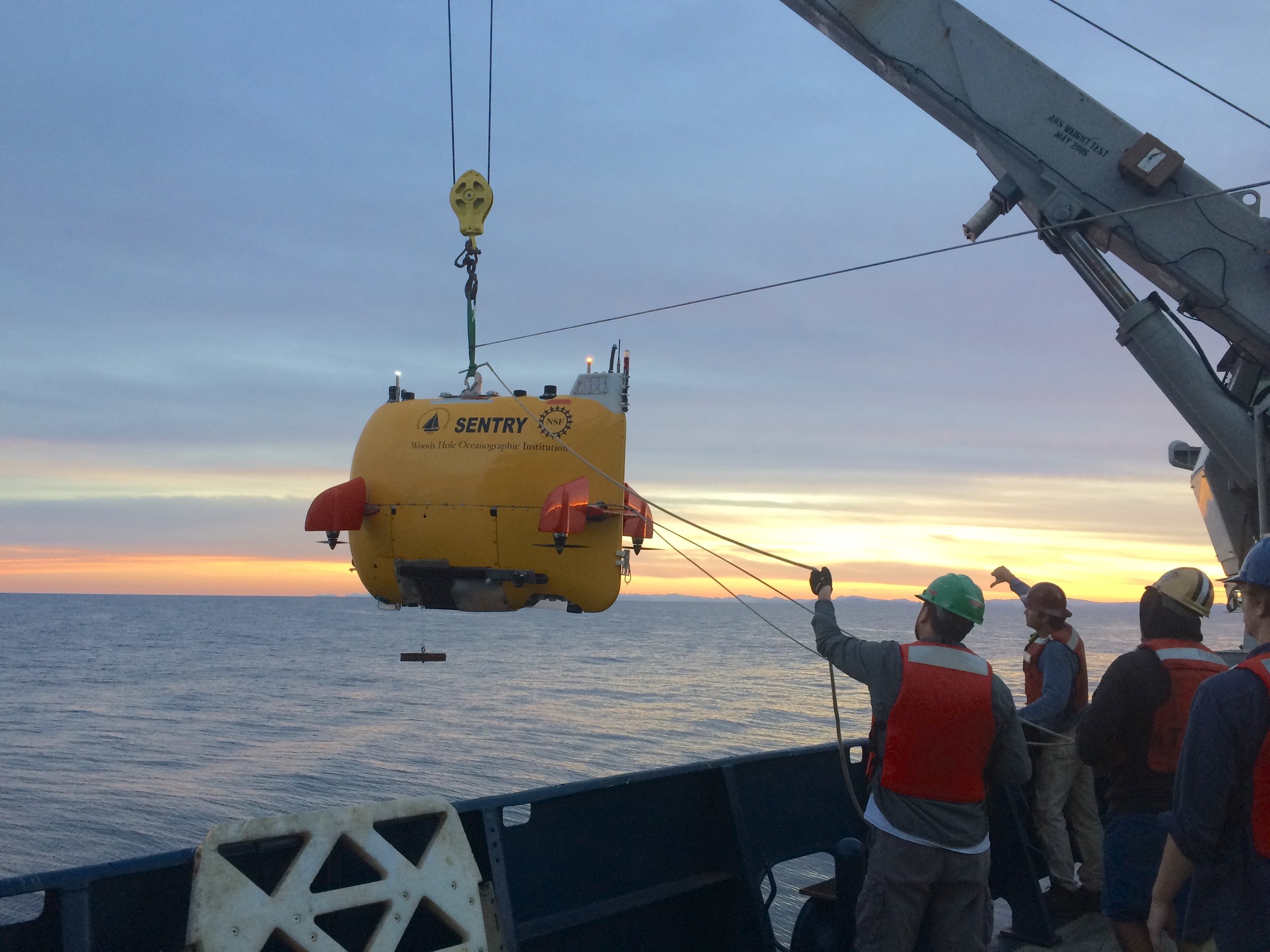

Identifying targets and making discoveries - AUV SENTRY

Exploration and discovery in the deep ocean requires a lot of planning. The ocean accounts for 71% of Earth’s area. The deep ocean, defined loosely here as depths 1000m and greater, accounts for a disproportionate amount of the ocean volume yet most of this habitat is completely unexplored. Earth’s “inner space” is thus a frontier for discovery.

The entire ocean floor has been mapped (remotely) at a resolution of 5 km, meaning we can visualize features larger than 5 km (~3 miles). For context, this distance is just shy of double the length between the Lincoln Memorial and the Capital Building in Washington DC (~3 km or 1.9 miles). Imagine trying to navigate your way through a city if your map only contained landmark that more than 5 km in length!

Only about 0.05% of the seafloor has been mapped using high-resolution sonar, meaning that for the vast majority of the deep sea, features less than 5 km in size are invisible. Thus, when working in the deep sea, a significant challenge stems arises from the lack of high-resolution maps. Such maps provide geological context and provide insight into potential chemical and biological characteristics to help target features/collections of interest. High-resolution mapping is thus a fundamentally important component of both science and exploration missions.

So, how do we obtain high-resolution maps of the seafloor? Maps having better than 5km resolution can be obtained using shipboard multibeam sonar surveys. But, the highest resolution maps can only be obtained through near-bottom mapping and that is best done using autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). These AUVs are equipped sophisticated instrumentation and sensors that generate data that allow comprehensive habitat characterization. On this expedition, we are fortunate to have the AUV Sentry on board.

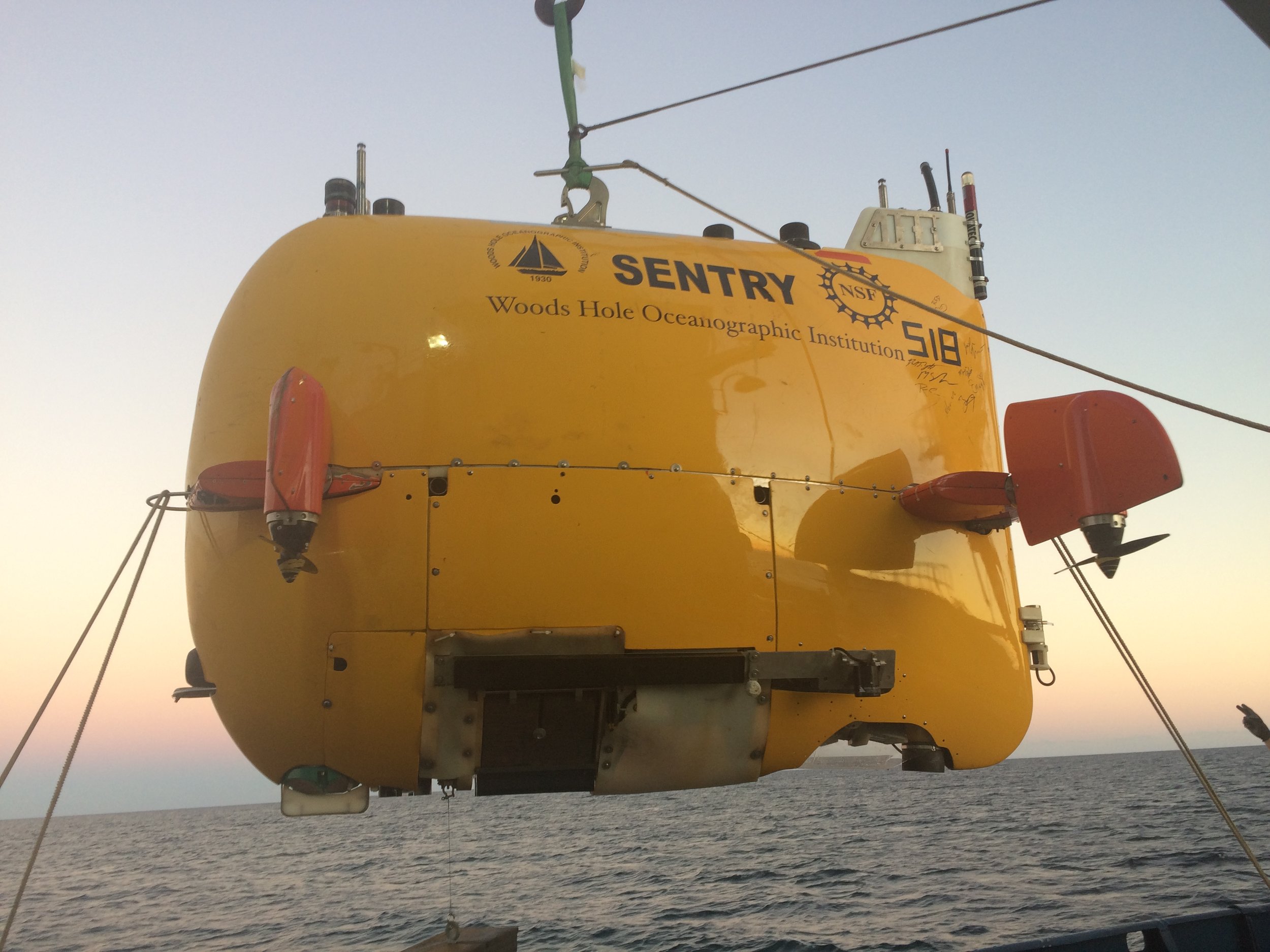

The AUV Sentry is an asset of the National Deep Submergence Facility at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Sentry is a flexible platform that comes with exceptional mapping capabilities and an impressive suite of chemical sensors. The vehicle is rated to 6,000 m (19,685 feet) making more than 90% of the deep ocean with its reach.

Sentry has a multibeam sonar, a chirp subbottom profiler, and three high precision magnetometers for mapping. The vehicle also has a Seabird CTD (conductivity, temperature, depth) and a number of sensors including, optical backscatter, oxygen, and oxidation-reduction potential. Project specific sensors can be incorporated into the vehicle, as possible. Finally, the vehicle has a high quality digital still camera that allows it to collect images that can be stitched together to create photo mosaics.

The Sentry dives at night while the ALVIN dives during the day. The Sentry team generates maps that we use to plan and execute dives with the ALVIN as well as work in the water column. These maps help us hone our dive plan and more often than not, the maps identify new targets to explore and sample. The coordinated efforts of the ALVIN and Sentry teams accelerate our ability to explore these deep sea hydrothermally-impacted habitats.

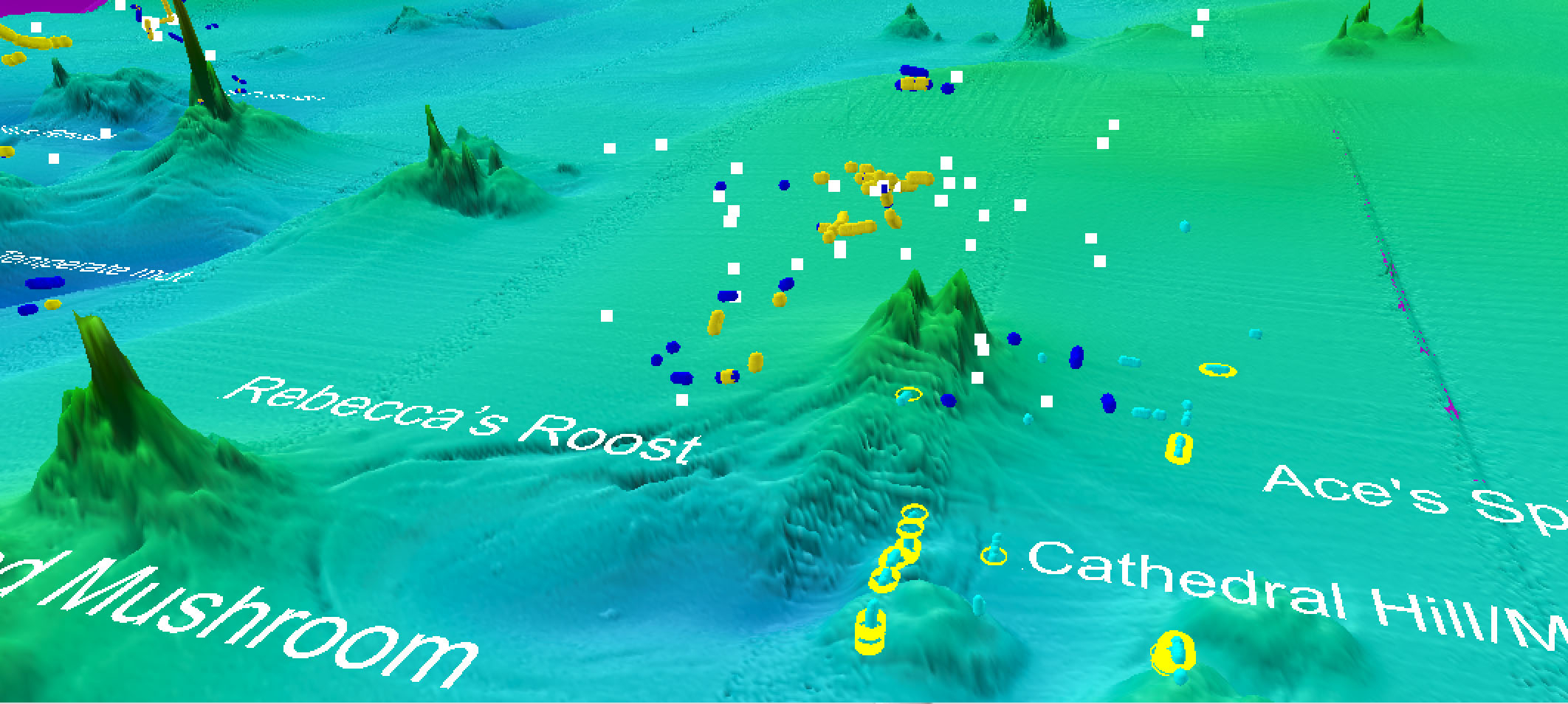

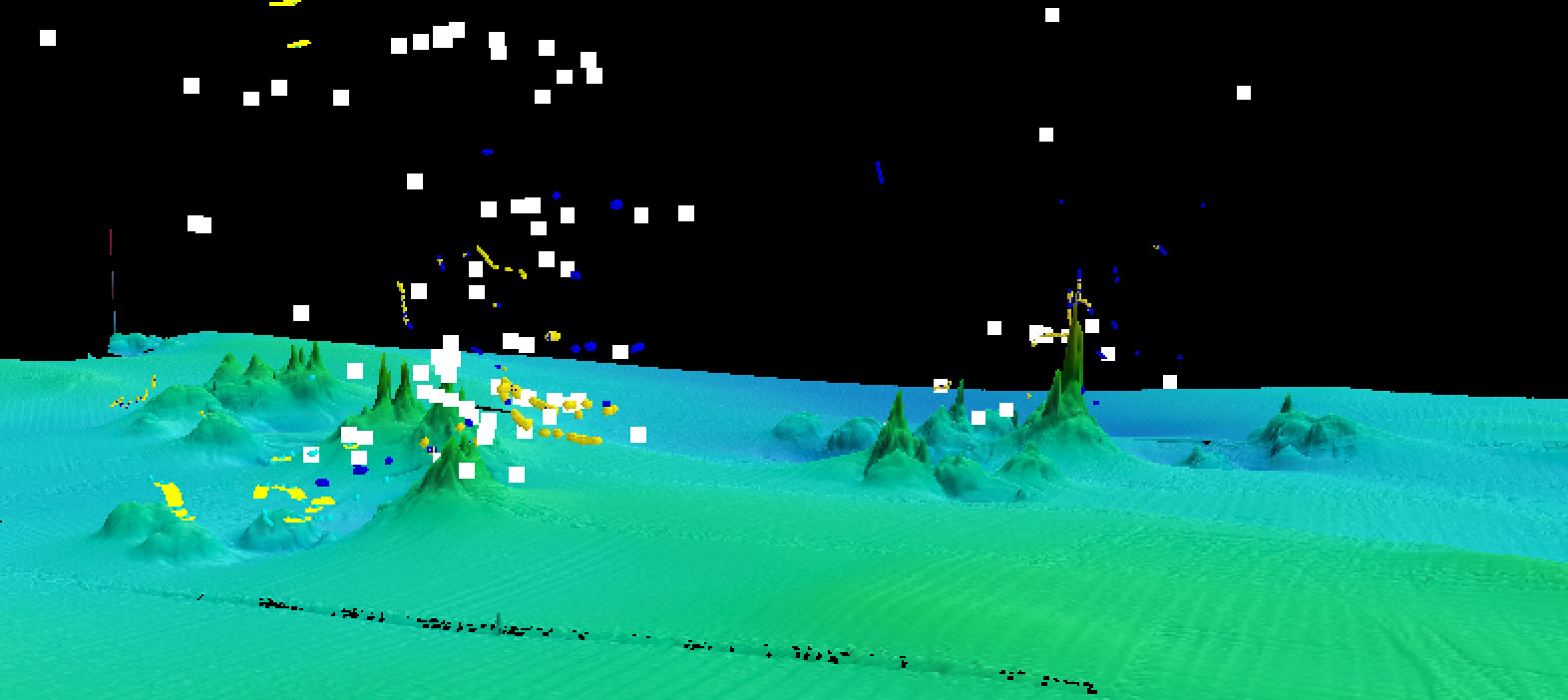

Sentry data informs every aspect of our science. Sentry data also helps us identify targets for water column exploration. Combining the bathymetric data with the data from chemical sensors generates incredibly informative maps that show hotspots of fluid discharge. By programming the vehicle to do vertical as well as lateral profiling, we obtain a three dimensional representation of these dynamic environments. The data show how hydrothermal fluids propagate through the system at sites we know.

More importantly, we can discover new targets in new areas and plan future research around those finds. The area on the left of the image below remains unexplored but is clearly a worthy target. We plan to visit this site in February 2019, when we return to the Gulf of California.